Influences

Morocco-Mauritania: The Dawn of a New Regional Order

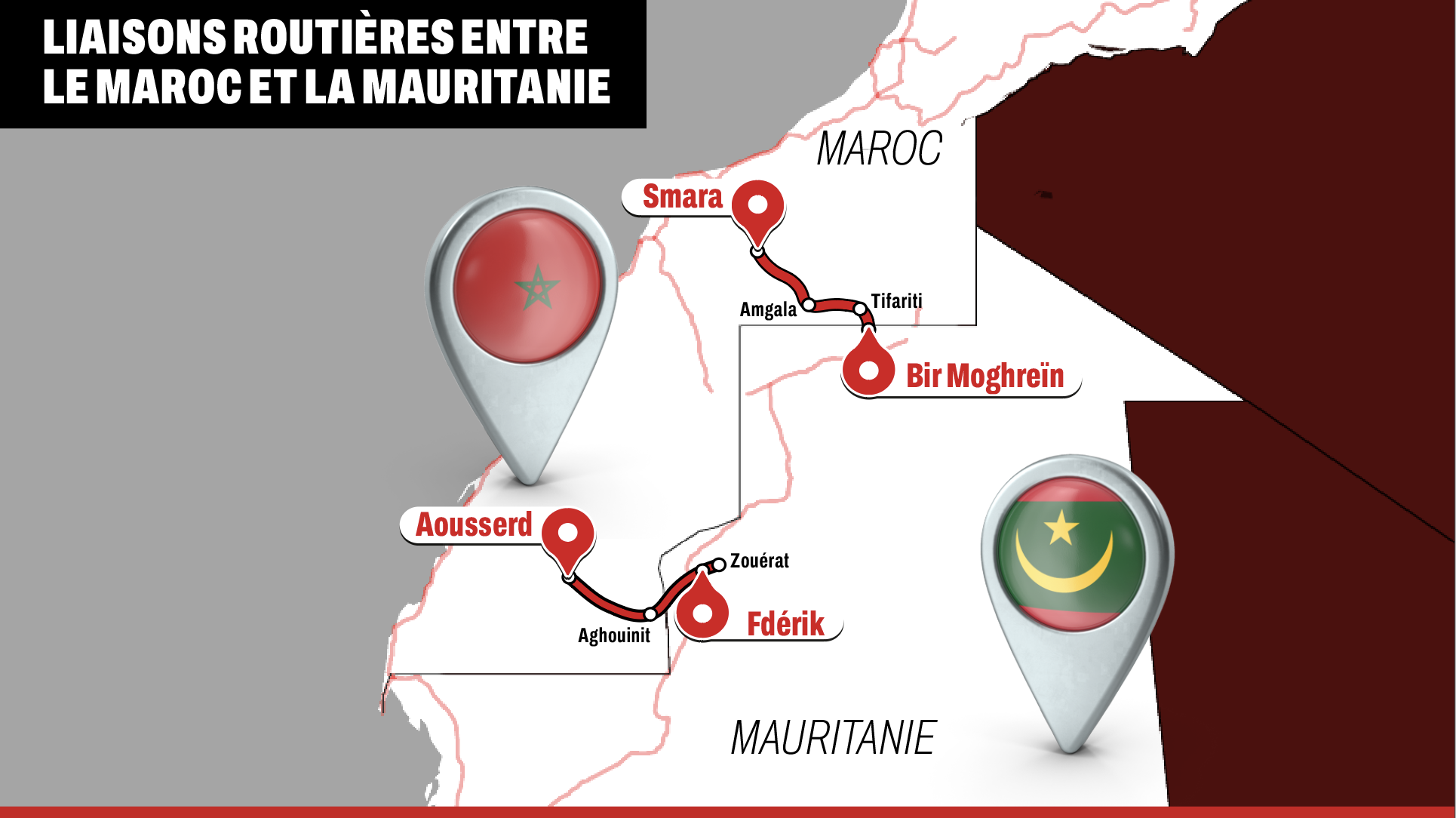

The two neighboring countries are currently working to establish a network of shared infrastructure—roads, electrical grids, and even gas pipelines. Three newly formalized land border crossings are paving the way for a sprawling economic corridor.

Everything began on November 13, 2020. On that day, the Royal Armed Forces (FAR) conducted a security operation to secure the El Guergarat border crossing, restoring free movement of people, goods, and merchandise between Morocco on one side, and Mauritania and sub-Saharan countries on the other.

The American recognition of Morocco’s sovereignty over the Sahara weeks later paved the way for large-scale regional initiatives. Since then, a new regional order began to take shape. Today, developments are becoming even more concrete.

Equipped with advanced customs control technology, this border crossing now sees an average of 200 trucks per day, translating to an annual average of 70,000 international road transport vehicles. This makes it a vital economic checkpoint and a main artery for goods heading to sub-Saharan countries, though it is nearing saturation.

This likely explains the recent “next-step” developments observed in recent weeks. At the end of January, during a working session of the Foreign Affairs Committee in the First Chamber, Foreign Minister Nasser Bourita stated that Morocco aims to transform this border post into a “strategic corridor” for land transport.

“We want El Guergarat to become an essential road hub, especially as land transport agreements are of great importance,” he said while presenting nearly 40 international agreements to the Committee, focusing on land transport.

The Kingdom is working to sign more such agreements to strengthen the crossing’s role as a strategic corridor, the minister emphasized, noting that “around ten bilateral agreements have been signed with friend countries.”

Two weeks earlier, Decree No. 2899-24 from the Ministry of Equipment and Water, updating the national road network for 2024, was published in the Official Bulletin on January 16. It specifies that National Road 3 (RN3) connects Dakhla to Aghouinit over 388 km, including 132 km of unpaved road.

It also highlights Provincial Road 1401 (RP 1401), linking Gueltat Zemmour to the Mauritanian border near Bir Moghrein over nearly 38 km (as an unpaved track). This provincial road connects RN1 in the Oued Eddahab province to the Mauritanian border via Bir Anzarane, Glibat El Foula, and Mijek over 382.8 km, including 119.2 km of unpaved road.

The town of Mijek lies close to Mauritania’s mining cities of Zouerate and F’derik. Two other routes link Morocco to the Mauritanian border: RP 1104, starting in Aghouinit and heading northwest for nearly 23 km (unpaved), and RP 1106, also starting in Aghouinit but extending south for 96.3 km (unpaved).

On the Mauritanian side, this formal and legal framework was complemented by an order issued on February 11 by the Minister of the Interior, designating 82 “bilateral” and “international” border points. This includes three new “international” crossings with Morocco: the first between Bir Moghreine and Smara, the second between F’derik and Aousserd, and a third further south at Taoujil, opposite Aghouinit.

In the Dakhlat Nouadhbou province, six international border points are listed, including El Guergarat (Point 55 km).

End of the Buffer Zone?

That said, officially, the Kingdom is now linked to its southern neighbor, Mauritania, and the rest of sub-Saharan West Africa via three land border crossings: El Guergarat (operational), Amgala (the newly designated crossing between Smara and Bir Moghreine, nearing completion), and a third between Aousserd and F’derik (still in the planning phase).

On February 19, a ceremony was held to announce the imminent commissioning of the Amgala border post, whose existence has been formalized by both sides. The provincial director of Equipment in Smara, quoted by MAP, stated that “the overall progress of the road axis (RN17 and RN17B) linking Smara to the Mauritanian border via the communes of Amgala and Tifariti, spanning 93 km, has exceeded 95% completion.”

Notably, Amgala and Tifariti lie beyond the security wall. It is worth recalling that before 1976, Tifariti was a town inhabited by roughly 7,000 residents, who abandoned it starting that year. Officially, “this project will enhance road connectivity between Morocco and Mauritania with the aim of opening a second border crossing, particularly as it will provide road users with a high-quality transport axis.”

However, economically speaking, Bir Moghrein remains a small locality of barely 3,500 inhabitants as per 2023 estimates (the last population census in Mauritania dates back to 2000). Thus, its current economic significance is minimal.

Politically, however, it carries far greater weight. The immediate implication is another demonstration of Mauritania’s “de facto and implicit recognition” of Morocco’s sovereignty over the Sahara. This aligns with other large-scale infrastructure projects, such as the recently finalized electrical interconnection between the two countries and the Atlantic Africa Gas Pipeline.

Additionally, as officially stated, “this road will also promote economic activities and socioeconomic development in the province, create jobs, and consolidate stability for the populations in the communes of Amgala and Tifariti.” Enough said. Morocco is actively resuming civilian activities in these two localities.

“Union of Iron and Hydrogen”

In short, heading south toward Zouerat, this route gains significant economic relevance and becomes profitable. Zouerat and F’derik, neighboring mining towns, have populations of 62,000 and 11,600 respectively (based on 2023 estimates).

The economic prospects expand further if Mauritanian iron—or at least a portion extracted from this region—is exported via the nearest port, Dakhla Atlantique, or if both countries collaborate to process it locally.

This evokes the “Coal and Steel Union” that laid the groundwork for the European Union. What might a “union of iron and hydrogen” look like in the context of Africa’s burgeoning continental free trade area (AfCFTA)? Notably, Morocco’s National Office of Hydrocarbons and Mines (ONHYM) holds a 2.3% minority stake in Mauritania’s SNIM (National Industrial and Mining Company).

This potential grows as F’derik and Zouerat will also be connected via a second planned road route passing through Aousserd and closer to Dakhla. Unsurprisingly, the significance of these routes extends far beyond Mauritania, as emphasized by Amgala commune president Fatima Sayeda, quoted by MAP: “This road aligns directly with the Atlantic Initiative launched by His Majesty King Mohammed VI, which aims to foster regional integration by facilitating Sahel countries’ access to the Atlantic Ocean.”

This initiative seeks to provide landlocked Sahel nations—Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad—with direct Atlantic access. By enabling this through its territory, Morocco positions itself as a critical logistics gateway between sub-Saharan Africa and global markets, amplifying its regional influence.

All parties agree this strategic project acts as a logistical bridge linking Morocco, Mauritania, and other African nations, bolstering economic development at regional and continental levels.

While awaiting the completion of the second route, this first axis—as noted earlier—integrates the buffer zone into the broader framework, reinforcing Morocco’s authority over its territory and border posts.

A new territorial network is emerging, anchored by three hubs: Dakhla, Smara, and Bir Anzarane. Its economic goals are twofold: alleviating pressure on El Guergarat (where TIR truck traffic surged over 180% between 2019 and 2024) and reducing travel time between Morocco and the Sahel.

Gradually, a commercial and economic corridor is taking shape. Agricultural and manufactured goods flow from Morocco to the Sahel, while minerals and raw materials are exported globally via the new Dakhla Atlantique port.

The developing infrastructure promises stability, attracting investment and fostering growth—a holistic stabilization of the region. Enhanced regional connectivity also strengthens cross-border security monitoring, curbing illicit activities in this historically volatile area.

This necessitates security cooperation among regional states—a dynamic increasingly favored by recent political shifts in the Sahel. Moreover, many elites in these nations are educated in Morocco, and the Kingdom—after modernizing its military capabilities—is poised to secure these routes with robust aerial coverage (drones, satellites), as demonstrated during the 2020 El Guergarat operation.

In essence, Morocco’s geostrategic repositioning is drawing global interest. The EU views it as a stable ally and a stabilizing force along Europe’s southern frontier. The U.S. sees Rabat as a gateway to Africa, while China eyes regional stability to expand its influence on Africa’s Atlantic coast.

Another regional player, the UAE, is speculated to be directly involved, particularly in Mauritania. Together, these shifts herald a nascent regional order whose full scope remains unfolding.

The upcoming joint Moroccan-Mauritanian High Commission, scheduled for March in Nouakchott, may shed further light on these developments.

Terrorism as a Braking Element

As the Sahel-Atlantic economic corridor gradually takes shape, Morocco is becoming the target of terrorist plots. Earlier this year, truck drivers were attacked in Mali—an incident far from isolated—and weeks later, a terrorist cell was dismantled near Casablanca, just before it could carry out its attack.

Last week, another terrorist network was neutralized. Its members, spread across multiple cities, were on the verge of committing an extremely dangerous act. Thorough investigations by Morocco’s BCIJ (Bureau of Judicial Investigations) confirmed a direct link between these groups and the ISIS-affiliated terrorist organization in the Sahel.

Weapons discovered in a hideout in Errachidia province were wrapped in Malian newspapers. Among the network’s members—operating under the command of Libyan national Abderrahmane Assahraoui—was an Algerian citizen. The seized weapons and equipment had been supplied and dispatched by this high-ranking ISIS official of Libyan origin in the Sahel region.

This once again underscores the urgent need to establish communication infrastructure in the area, both to combat terrorism and to control arms trafficking and other prohibited goods.