Influences

Geostrategy: Why Morocco Has Permanently Turned Its Back on the Arab Maghreb Union

Launched in Marrakech 36 years ago, the Kingdom has gradually lost interest in the Arab Maghreb Union (UMA). The challenges it faces, its ambitions, and its development strategies far exceed this framework. Not to mention the persistent tensions with Algeria.

According to data revealed by the third national survey on social ties conducted by the Royal Institute for Strategic Studies (IRES), Moroccans primarily identify themselves as “Muslims,” followed by “Moroccans,” then as Arabs, and in fourth place as “Maghrebis” and “Africans” thereafter.

The survey report, which has just been published, highlights “a cosmopolitan vocation: Maghreb, Africa, the world. These extranational identity markers have, moreover, experienced a remarkable rebound between 2011 and 2023.” Today, Moroccans consider themselves, so to speak, “more Maghrebi” and “more African,” but, from an identity perspective, they refer less to Islam and Arabness.

The Maghreb is strongly present in the minds of Moroccans, but likely only from a geographical standpoint. The reality is that, 36 years to the day after the proclamation of the Arab Maghreb Union (UMA), the Maghrebi ideal is drifting further away year by year.

While, some twenty years ago, the UMA was a strategic option to the point of explicitly including it in the preamble of the 2011 Constitution, “The Kingdom of Morocco, a united, fully sovereign state, belonging to the Greater Maghreb, reaffirms the following and commits to it: working towards the construction of the Maghreb Union as a strategic option (…),” it has had to revise its priorities, especially over the last decade.

There have been many changes. For reasons inherent to the organization’s own statutes, whose decisions are made at the Summit of Heads of State—which has not convened since 1994—as well as for other reasons related to the dispute over the Moroccan Sahara, the UMA has been completely paralyzed since then. This is further compounded by the fact that out of the 37 agreements and treaties of the UMA, barely 8 have been ratified by all five countries.

The latest initiative to relaunch a Maghreb without Morocco, a project categorically opposed by Mauritania and a faction of the Libyan ruling power, certainly does not improve the situation and definitively sounds the death knell for this regional organization. And this is despite the fact that, institutionally, the project still exists and a new secretary general has just been appointed.

Nevertheless, since March 2024, during the Gas Summit, the Algerian neighbor decided to create an alternative structure to the Maghreb, involving Tunisia and a Libyan faction.

A first summit-level meeting was held shortly thereafter, and a second summit is scheduled for next April. The Kingdom, undoubtedly sensing such shifts, has decided to step back over the past decade, focusing instead on reconnecting with its African roots.

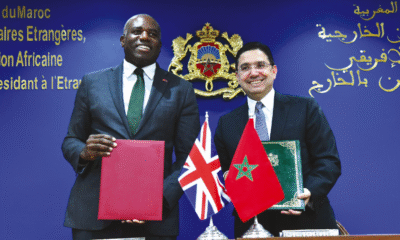

This has led to several royal tours across Africa and the signing of over 1,000 cooperation agreements and treaties with countries on the continent. This process continued with Morocco’s reintegration into the African Union (AU) in 2017, followed shortly after by its request to join ECOWAS.

Redefining Priorities

Today, the two flagship initiatives launched by the Kingdom—the Atlantic Africa Gas Pipeline and the Sahelo-Atlantic Initiative—are part of a much broader regional space, and its relations with Mauritania have improved dramatically in recent years.

The two countries are now connected by three border crossings, an electrical interconnection, and soon a gas interconnection, in addition to telecom links, and are preparing to embark on even larger projects, the scope of which will likely be announced during the upcoming High Joint Commission.

The attentive observer will have noted the openly evident distancing among the countries that make up the UMA. This is, after all, expected, as Algeria has always worked to impose a de facto UMA of six since Bouteflika’s first term.

Today, tensions between the two poles of the region—Morocco and Algeria—have reached a point where serious studies, such as the one recently published by Oxford Analytica, conclude that “tensions between Morocco and Algeria show no signs of easing, although both sides have sought to avoid war.” It adds, “the possibility of direct conflict remains modest, but several factors could increase this risk in the coming years.”

It must be said that while the UMA promised a common market of nearly 100 million people, trade among member countries has never taken off. In 2025, intra-Maghreb trade accounts for less than 5% of the total trade of member countries.

Algeria’s recent decision to sever all forms of relations with Morocco, including banking domiciliation, has brought direct trade to a complete halt. Both parties must now go through a third country to exchange goods on a reduced scale.

For Morocco, which has developed free trade agreements with the EU, the United States, and African partners, the UMA no longer offers significant economic advantages compared to these alternatives. According to some analysts, faced with the Maghreb’s stagnation, the Kingdom has redefined its priorities.

It has strengthened its Atlantic anchor and established itself as a key player in sub-Saharan Africa through investments (in banking, telecoms, phosphates) and initiatives such as providing Sahel countries with access to the Atlantic. “These axes offer immediate benefits and align Morocco with global dynamics, far from the UMA’s aborted regional ambitions,” it is noted.

Similarly, it is emphasized that “recent Maghreb initiatives, such as the Algeria-Tunisia-Libya meetings in 2024, have deliberately excluded Morocco, reinforcing the perception that the UMA, even if revived, could operate without or against its interests. This pushes Rabat to lose interest in a structure where its influence is contested.”

Thus, in a global geopolitical context, Morocco now capitalizes on strong alliances, including recognition by several countries of its sovereignty over the Sahara, its military partnerships with Israel post-Abraham Accords, among others, and on issues such as energy security or the fight against terrorism, where the UMA plays no role.

In short, the organization no longer meets the current challenges faced by the Kingdom. Its interests and ambitions go far beyond.

A Missed Momentum

Two decades ago, Algerian gas could have contributed to a rapid industrial takeoff for Morocco. Today, the Kingdom is on the verge of becoming an energy exporter in the form of green hydrogen and its derivatives.

The Algerian market could have, a few years ago, become a major outlet for Moroccan products. Today, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) opens up much more dynamic markets, with diversified economies and diverse needs, but above all with high levels of growth.

About fifteen years ago, one of the most integrated projects the two countries could have considered would have been the joint exploitation of the Gara Jebilet iron mine, with the possibility of creating an easily exportable steel industry or producing ammonia at highly competitive costs, thus fertilizers to enhance Algeria’s vast agricultural lands.

These are projects Morocco has not abandoned; it has simply changed partners. It will produce its ammonia locally, and even steel.

Morocco could have, and it was undoubtedly considered, relied on the Algerian market to develop its tourism sector. Again, without this market, which is now experiencing a loss of purchasing power, the Kingdom has become Africa’s top tourist destination.

Examples could be multiplied at will, but the fact is that the Kingdom has managed to take off economically without needing a Maghreb free trade zone, a customs union, or even a common market that was supposed to solidify the integration of Maghreb economies and should have been operational for more than two decades already.