Influences

Brutalism: Concrete, My Beautiful Obsession

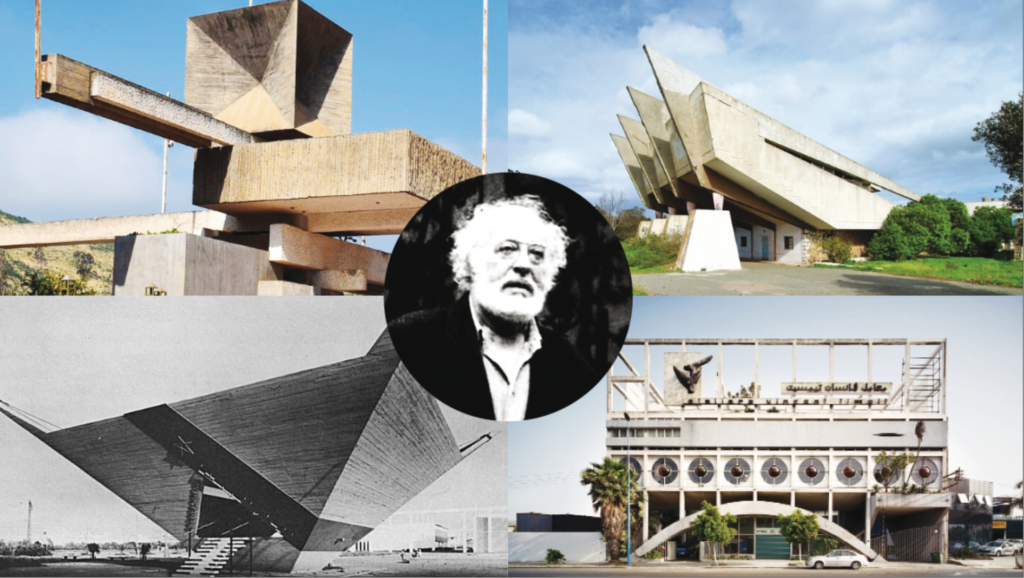

As the film The Brutalist reignites interest in radical architecture, its legacy in Morocco – championed by figures like Jean-François Zevaco – treads a fragile line between admiration and neglect. A symbol of bold modernism, it now battles the erosion of time and urban apathy.

Currently in movie theaters, The Brutalist defies conventions in American cinema. With three Golden Globes and ten Oscar nominations, this ambitious epic traces the life of a fictional Holocaust survivor and Bauhaus-trained architect who emigrates to post-war America. Led by Adrien Brody, the film’s sprawling runtime, intellectual rigor, and grand scale set it apart as a striking anomaly.

Coincidence or not? The Brutalist arrives as the architecture it portrays – championed in Morocco by figures like Jean-François Zevaco – faces political scorn. Donald Trump, partial to glitzy glass towers and casinos, has dismissed Brutalism as unworthy of representing America. Its offense? Falling short of his narrow standard of “beauty.”

Nothing but Ugliness?

Brutalism hinges on unembellished architectural expression, stripped of ornamentation – a direct response to functional needs, prioritizing clarity of form over aesthetic flair. Though its name derives from béton brut (raw concrete), the movement is not defined solely by the material. A building is Brutalist not because it contains raw concrete, but because it makes the material the structural and conceptual core of the design, unapologetically embracing its weight, texture, and monolithic presence.

Brutalist structures are defined by simple yet imposing volumes, bold lines, and the deliberate exposure of technical elements: exposed columns, cantilevered slabs, pillars, and stark plays of light and shadow created by minimal openings. The style often showcases complex, sculptural forms enabled by innovations in formwork and prefabrication techniques.

This architectural language spread globally, leaving an indelible mark from the 1950s to the 1970s, before gradually fading from favor – even sparking backlash. In Morocco’s architectural history, Brutalism became the voice of a nation rebuilding itself, particularly in Agadir after the devastating 1960 earthquake.

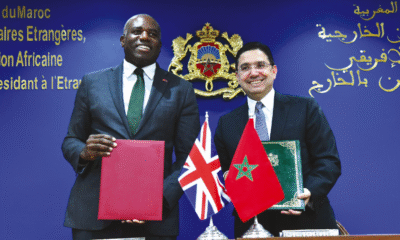

Among architects who remained in post-Independence Morocco, only those committed to shaping a new nation stayed to leave their mark. Visionaries like Henri Tastemain, Éliane Castelnau, Patrice Demazières, Abdesslam Faraoui, Élie Azagury, and Jean-François Zevaco reshaped the nation’s architectural identity with bold, forward-thinking designs that endure as both symbols of modern ambition and relics of a contested era.

Monumental Aesthetics

Flashback. Under Michel Écochard’s leadership, Casablanca’s urban planners crafted the city’s second urban development plan, ambitiously aiming to expand, modernize, and dismantle its sprawling shantytowns. Écochard, a visionary, prioritized mass housing solutions, notably in the working-class district of Hay Mohammadi’s Carrières Centrales. This area once concentrated Casablanca’s most significant Brutalist landmarks – many now vanished. Among them was the National Tea and Sugar Office, a demolished relic of the city’s brief but fervent Brutalist era.

Brutalism’s stark aesthetic enabled the creation of structures that fused functionality with bold expression: covered markets where concrete canopies filtered sunlight, administrative buildings flaunting raw load-bearing structures, and housing complexes marrying modular efficiency with livability. More than a style, Brutalism became a design philosophy – architecture not as ornament, but as an unflinching assertion of structural truth.

Jean-François Zevaco, widely regarded as one of Morocco’s greatest 20th-century architects, embodies this duality. To some, his work transcends architecture, veering into sculptural art. In Casablanca – where his career began in 1947 – his concrete marvels still stand along labyrinthine boulevards, weathered by time and choked by the residue of heedless urban growth.

What remains of Zevaco’s singular imprint? Of his gravity-defying structural feats, his meticulously carved lattice screens, his sculptural concrete bursts? What endures of this visionary architectural language, born in postwar Morocco’s experimental fervor, when the nation became a laboratory for avant-garde modernity? In four stops, we trace – inevitably incompletely – the legacy of a “modernity lab” now fading into memory.

Imposing Structures

First, his magnum opus – the project that brought him both acclaim and controversy – still rises defiantly at the crossroads of Casablanca’s major boulevards. But under siege by globalized storefronts, Villa Suissa has become an architectural hermit crab, forced to cloak its daring design beneath the trappings of commerce and consumerist demands.

Originally conceived as a flamboyant symbol of its patron, developer Sami Suissa, the villa was transformed by Zevaco’s virtuosic touch into a defiant declaration, a joyful middle finger to rigid conventions. Uncompromising in its graphic exuberance, Villa Suissa shattered architectural norms of its era. With its jagged spires, boldly curved terraces, and suspended geometric forms, it seems plucked from a fever dream straddling pop avant-garde and futurist fantasy. Inside, Vincent Timsit’s visionary ironwork unfolds as a metallic cosmos – a realm of raw elegance where structural experimentation verges on extravagance.

Yet what remains of this modernist utopia? Renamed Villa Zevaco, the building survives only through commercial compromise: it now houses a high-end bakery-restaurant (Paul), a hushed theater of bourgeois brunch rituals where Casablanca’s elite gather, made-up and languid, beneath the glow of chic consumerism.

A Cruel Paradox

The irony is biting: this masterpiece of architectural radicalism, conceived as a defiant rupture, now languishes as a passive backdrop of bourgeois decor, its boldness reduced to a distant memory.

While Villa Suissa, drenched in fame, stands as a gleaming emblem of Zevaco’s legacy, the reality of his architectural heritage remains far more fragile. Behind this mirage of recognition, most of his works teeter on the margins of preservation, caught between oblivion and decay.

Take the striking Agadir Street Market, designed in 1972 amid fading Art Deco buildings. Beneath its interlocking concrete canopies – stacked with sculptural rigor – lies a cluster of vendor stalls. Their circular modules retain a modernity so startling it seems to defy time. The result is jarring: a Brutalist utopia and futuristic relic, now surrendered to the banality of daily life.

Beyond exceptional schools like Théophile-Gautier and Idrissi – where access is restricted – a handful of Zevaco’s public buildings endure in Casablanca. Among them, the AXA headquarters on Boulevard Hassan II, its façade a grid of diamond-shaped windows tapered with near-ornamental precision.

Yet for Zevaco, nothing is arbitrary. His architecture spurns cheap theatrics, rejecting flashy decorative gestures. Here, no compromises. These windows aren’t merely decorative: they choreograph light with sovereign intelligence – softening its glow here, diffusing its glare there – never succumbing to empty spectacle.

Meanwhile, the city marches on in apathy. Buses and trams race across asphalt, absorbed in their own rhythms, leaving Zevaco’s creations to converse with time, unseen by distracted eyes.

For the most intrepid – those whose curiosity borders on obsession – a visit to Vincent Timsit’s extraordinary workshops becomes an initiatory rite. This architectural flagship, stranded on Boulevard Moulay Ismaïl, feels plucked from a realm where modernist rigor dances with whimsy.

Everywhere, ingenuity thrives in subtle details: a hexagonal mailbox, protective grilles retracting with mechanical elegance into floors, crafted elements where function and beauty intertwine seamlessly.

Here, nothing is superfluous, nothing ornamental in the hollow sense. Every detail is calculated, calibrated, alive with a logic where pragmatism meets poetry. Yet in a city that builds by erasing, how long can these fragments of modernity withstand indifference?