Kingdom

March 8th Special: Feminist Movement – A New Generation, New Struggles?

The feminist movement in Morocco is witnessing the rise of a new generation of activists, marking an evolution in the struggle. While pioneers rely on the universal framework of human rights, younger activists are focusing on individual freedoms. Insights…

During the 1980s and 1990s, feminist associations multiplied, advocating for gender equality, with each specializing in distinct areas such as health, education, and legal rights. Since then, the feminist movement has evolved significantly, marked by substantial advancements in women’s rights.

From the fight for legal equality to demands for greater participation in economic and political spheres, women have succeeded in bringing the debate into the public arena.

While early feminists grounded their struggle in the universal framework of human rights and democracy – focusing on gender equality and non-discrimination – younger generations are now prioritizing individual freedoms. The cause remains shared, but the approaches differ.

The advent of new information and communication technologies in the early 21st century has provided fresh platforms for mobilization and awareness-raising, giving rise to a new wave of feminists. This so-called ‘connected’ generation distinguishes itself through its modes of engagement, notions of social justice, and communication channels, which diverge from those of their predecessors.

While respecting the achievements of earlier generations, young activists aim to break away from traditional movements. They advocate differently, adopting new forms of engagement to promote gender equality and denounce violence against women. Their approach is more targeted, leveraging virtual mobilization to reach a broader audience.

Early feminists focused on grassroots work and advocacy to be integrated into public policies – a struggle that, as Ouafa Hajji, president of Jossour, explains, “spanned over thirty years and resulted in improved women’s rights and the enactment of the Family Code in 2004. Today, mobilization must continue, embracing all forms of engagement.”

The next generation is here, and it acts differently…

Indeed, diversity remains not only a major asset for the feminist struggle but also a powerful driver of performance and success.

This underscores the necessity for intergenerational dialogue, as suggested by the Coalition Génération Genre Maroc (CGGM), composed of the Association Démocratique des Femmes du Maroc, the Fédération des Ligues des Droits des Femmes, and the Association Médias et Cultures.

Committed to strengthening the feminist movement by fostering dialogue between generations, the CGGM highlights in its 2024 study the importance of understanding how the coexistence of different generations influences feminist struggles and how creating synergies can ensure the continuity of the fight for women’s rights and gender equality.

While many activists have avoided addressing the issue of succession, some remain vague on the subject, stating broadly that ensuring effective succession requires fostering mutual understanding, sharing experiences, and cooperation between generations.

For others, the new generation is a sign of hope for feminism’s continuity. “Young activists want -and I understand them – to be independent. I think this is interesting; they work, with their own approaches, for shared causes,’ argues Ms. Hajji.

Indeed, online feminism – ‘connected activism’ – emerged after the #MeToo movement and has embraced exclusively digital feminist advocacy (MASAKTACH, HACHAK, Diha F’rassek, #MeTooUniv…).

The web and social media, particularly digital platforms, represent for these non-institutionalized activist groups an ‘oppositional space’ that aspires to create ‘lightweight,’ flexible, non-institutionalized, and more horizontal organizations.

For Bouchra Abdou, director of the Association Tahadi pour l’Égalité et la Citoyenneté (ATEC), “these young activists act in a targeted manner, working on specific issues such as digital violence, inheritance rights, rape, abortion rights, etc.

It would be beneficial for the founding generation of early associations to integrate them and enable collaborative work.” An idea shared by Ouafa Hajji, who believes “young activists could be involved in communication and networking efforts to reach a broader audience.”

In other words, a complementary, non-hierarchical intergenerational movement should be considered. Currently, pioneering associations still face challenges in integrating, retaining, and securing the loyalty of younger members. To achieve this, Ouafa Hajji argues that “we must reorganize by revising internal statutes and innovating operational methods to move beyond bureaucracy and pave the way for youth.

I believe this is a natural evolution that will occur to make space for the younger generation.” Bouchra Abdou also thinks “young profiles should be promoted, and associations should not be tied to a single name!” In her organization, opportunities are given to young social workers, for example, to represent ATEC and engage on issues they understand deeply due to their grassroots experience.

The cause is shared, but the approaches differ. Feminists across generations agree that their struggle aims to promote equality and justice, eliminate all forms of legal, social, economic, or cultural discrimination based on gender, strengthen women’s autonomy, and empower women through control over their own lives.

However, they assert clearly that creating a homogeneous movement encompassing all this diversity is impossible. Merging tendencies into a single coherent movement seems unfeasible, but fostering dynamic and sustainable intergenerational collaboration could be considered – a way to pass the torch forward.

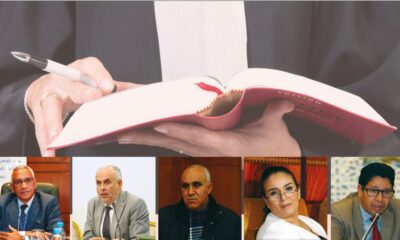

The four generations of feminists…

The evolution of the feminist movement in Morocco over the last three decades reveals four generations of feminists fighting against various forms of discrimination. The founding generation of early associations embodies a universal feminism.

Their demands focus on integrating women’s issues into the broader project of democratization and the rule of law. Following the 2000 Casablanca march, a counter-movement emerged: a ‘religious/Islamic feminism’ defending Moroccan Muslim identity and protecting the family and Moroccan women against perceived ‘enemies’ and Western influences.

This collective action prioritizes the socioeconomic needs of ‘ordinary,’ ‘vulnerable,’ and ‘illiterate’ women. This feminism advocates complementarity over equality. In 2011, the Arab Spring generation, largely composed of young students and researchers, promoted a pragmatic feminism.

These feminists prioritize socioeconomic rights and individual freedoms, engaging in vertical collective action. Online feminism – ‘connected activism’ – emerged post-#MeToo, adopting exclusively digital advocacy.

Social media became an ‘oppositional space’ aspiring to create ‘lightweight,’ flexible, non-institutionalized, and more horizontal organizations.